Previously, IGS Insights explored the future of US-based cloud services such as Google Analytics in Europe, where the ‘clouded legal uncertainty’ surrounding the nature of EU-US data transfers was made apparent. The lack of clarity in this area of data protection law has led to companies such as Meta calling out for more stringent arrangements for data transfers between the EU and the US. Calls for change seemed to be answered when the Commission and President of the United States declared an “agreement in principle” of a Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework on 25th March this year.

This article will briefly explore the history of data transfer arrangements between the EU and the US, and consider whether the proposed framework is a straightforward path to certainty or whether there will still be complexities and issues which will remain unresolved.

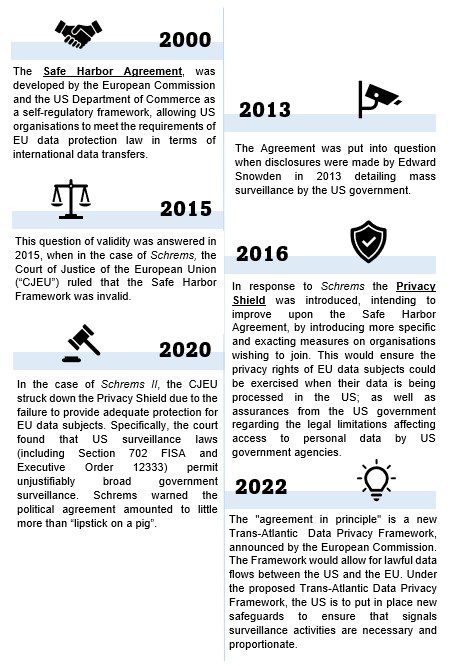

The above timeline gives a brief history of data transfers between the EU and the US. The case of Schrems II highlighted significant roadblocks to achieving a data sharing framework with the US, which will need to be addressed in the new framework. The most notable of these include:

- The requirements of US national security, public interest, and law enforcement to interfere with the fundamental rights of EU data subjects;

- The principle of proportionality was not satisfied – US surveillance programmes are not limited to what is ‘strictly necessary’;

- The Ombudsperson mechanism that had been in place under the Privacy Shield, did not provide the data subjects with a cause of action before a fully independent body. The body that existed had limited authority.

Lack of legal certainty?

Standard Contractual Clauses (“SCCs”) are just one of the methods available for a lawful transfer of personal data to a third party, however in practice, they are by far the most common method of transfer to third parties. With the abolition of the EU-US Privacy Shield, the Court in Schrems II ruled that SCCs were still valid; however, the judgment stated that companies must verify, on a case-by-case basis, whether the law in the recipient country ensures an adequate level of protection for data subjects; which is achieved through a Transfer Impact Assessment (“TIA”). Where it doesn’t, that country must ensure there are appropriate technical and organisation measures which exist to ensure the safe processing of the data in question. The proposed SCCs however, have not been without their drawbacks. The need for an extravagant TIA is burdensome and disproportionally impacts small and medium-sized firms. Additionally, whilst SCCs have been adopted as the status quo, recent cases seen by European Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) have highlighted both lack of certainty by the DPAs surrounding the application of Schrems II, and also by many EU companies who have been falling far short of implementing the required appropriate technical and organisational measures when transferring data to the US.

Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework (TADPF)

An “agreement in principle” for a new Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework was announced on 25th March. In practice this agreement should allow for lawful data flows between the US and the EU, without the need for additional lawful transfer mechanisms which already exist under the GDPR. A press release from the White House outlined that the new framework ensures that:

- Signals intelligence collection may be undertaken only where necessary to advance legitimate national security objectives, and must not disproportionality impact the protection of individual privacy and civil liberties;

- EU individuals may seek redress from a new multi-layer redress mechanism that includes an independent Data Protection Review Court that would consist of individuals chosen from outside the US government who would have fully authority to adjudicate claims and direct remedial measures as needed; and

- US intelligence agencies will adopt procedures to ensure effective oversight of new privacy and civil liberties standards.

The new Framework is intended to revive and enhance the abolished Privacy Shield. Participating companies will be required to adhere to the existing Privacy Shield Principle, including the self-certification requirement.

What next?

On the face of it, the statement seems to a be a positive step in achieving the free flow of personal data between the EU and the US. However, critics have already raised concerns. The Swedish DPA, Integritetsskyddsmyndigheten, states that the new framework must address the shortcomings identified by the European Court of Justice in the Schrems II judgment if it is going to stand a chance of withstanding legal scrutiny; in particular, in limiting the collection of personal data for purposes that have to do with national security to what is strictly necessary and proportionate and to create effective remedies for the data subjects. Data privacy activist, Max Schrems, suggests that it is likely that the matter will end up back before the European Court of Justice within months of a final decision.

From the Statements released so far, several obstacles seem apparent:

- Surveillance laws – as it currently stands the US is not planning to change its surveillance laws, the statement simply outlines foreseen executive reassurances (using EU language like “proportionality”). It is unclear how this would pass the test by the CJEU, as it has already been held that US surveillance activities have not been deemed to be “proportionate”: previous agreements failed twice in this respect. The case of FBI v Fagaza adds further concern in this area having strengthened the rights of surveillance authorities to access personal data of US residents.

- Proportionality – two key issues arise with this GDPR standard. The first, is that US surveillance operations are mostly classified and therefore US state secrets would have to be disclosed in order for proportionality to be assessed, which would deem this test problematic. The second, is that US case law does not use terminology such as “proportionality”, neither does it recognise the proportionality test used in the GDPR under a similarly comparable regime; ultimately making this assessment much more difficult.

- “Agreement in principle” – currently the statement is merely a political announcement; it does not constitute a legal framework. Therefore, for companies nothing has changed; appropriate actions must still be taken when transferring data to the US. As NOYB suggests, until a text is published, it is likely to generate even more legal uncertainty. This is partly due to the term “agreement in principle” meaning that lawyers still need to find solutions to the problems raised by the European Court of Justice. So far, there have been no functioning solutions despite the two years of discussions.

- Legal scrutiny – there are already doubts that this agreement, once committed to text, will survive legal scrutiny. NOYB have already stated that they would challenge any new agreements that do not meet the requirements of EU law. Schrems has suggested that the agreement as it stands is too similar to an approach that has ‘failed twice before’, and that this is a ‘patchwork’ with no substantial reform on the US side.

Conclusions

Although the agreement is seen as a ‘positive step in the right direction’, there are many stumbling blocks in which this framework could face before it is introduced into law. Only the proposed redress mechanism seems to respond to the criticisms made in Schrems II; the matters of surveillance and proportionality still seem to be lacking in clarity. However, it is hard to properly critique this framework until a full text is available, and this is unlikely to happen for at least several months. Despite these stumbling blocks, EU DPAs have declared their readiness to support the Commission in ensuring a new framework meets the requirements of the GDPR which may suggest a pressing need for further clarity on data transfers to the US; recent cases in the EU seem to suggest this is the case. Nevertheless, enthusiasm among EU countries could provide benefit even if the creases in this framework are not ironed out; a spotlight on this problematic area of data protection law might lead to well-deserved focus on the ongoing issue of EU-US data transfers in a world where most of the big tech providers are based in the US.